NOTE: Not all the hyperlink footnotes have been uploaded to this page yet.

Israel Ludlow's Whitehead-powered Aeroplane (& How it Took Off on the Smithsonian Institute's Front Lawn)

Israel Ludlow (1873-1955) was the son of Brig. Gen. Benjamin C. Ludlow of Cincinatti. The Ludlows were a prominent family in Ohio. Indeed, another ancestor and namesake, Israel Ludlow, founded and planned the city of Dayton (the Wright brothers' home town).

Ludlow's father was well known. This helped his son later in many ways. Gen. Ludlow had been a hero of the American Civil War, liberating an area of eastern Virginia where his son later directed an aeronautical exposition and convention. (In that context, Gen. Ludlow is best known today for his efforts to free slaves.) Young Ludlow's aviation experiments were facilitated by workshops supplied by the War Ministry, liaison officers, sailors and ships by the Navy and even cavalry horses by the Army.

Israel Ludlow attended elementary school in Texas, studied law at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, graduated in the class of 1895 and took up legal practice in New York the same year. There, he was both active in local politics and as a social reformer. One of his most famous cases was against the NYPD where he represented blacks who'd been mishandled in police custody. He stood up to Police Commissioner York who tried to intimidate him and prevent him from cross-examining police witnesses. When Ludlow later sustained an injury putting him in a wheelchair, he helped pioneer access to public buildings for handicapped persons, all the while pushed by a black nurse. He was also a vegetarian.

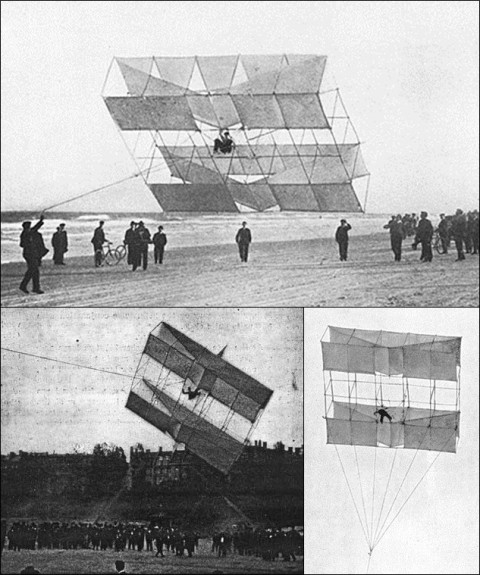

It's reported, Ludlow's interest in aeronautics began in his college days in the early 1890s. It's not known exactly when he started planning and building aircraft. Various articles quote as having a collection of kites, having performed aerodynamic and equilibrium experiments on aircraft models, experimented with a powered model driven by a wind-up rubber band, and being forced to throw away 60 aircraft models when he ran out of space to store them. They also report him having experimented with "tetrahedral kites" and a man-carrying glider (with which he flew 25 yards at a height of 12 feet at Riverside Avenue in New York) in the first half of 1905.

Ludlow's first steps towards powered flight were taken in 1905 by towing his manned gliders behind cars and boats, then attaching a motor to them. That same year, he also became associated with the newly-founded Aero Club of America.

For his experiments, Ludlow enlisted a pilot named Charles Hamilton. Financing was shared by his partners, Dr. Julian P. Thomas (a surgeon, balloonist, automobile fan and co-founder of the Aero Club) and Henry T. McIntyre of the Institute of Arts & Sciences in Brooklyn.

Charles K. Hamilton (1885-1914) was born and raised in Connecticut. At age 8, he tells of jumping off the barn roof holding his mother's parasol. Once he got a bit older, he first attached sails to a wagon and got it airborne, then built a manned kite and flew it up to 100ft.

As an adolescent, he finally took a ride on a real airship and decided to make flying his career. According to one source, in 1899 (at age 18), he started both ballooning and parachuting at shows. Soon thereafter, he married his first wife, Jennie Lugan, from Bridgeport, Connecticut. He then claimed to have lived in Texas for a while before moving back East.

The "who's who" of ballooning reports that Hamilton began working for Ludlow in 1903. Hamilton's obituary states it was 1904.

Hamilton and Ludlow flew both dirigable balloons and winged aircraft. On one occasion they borrowed the Cailifornia Arrow from Leo Stevens and planned to put on a show at Brighton Beach, New York. However, on that day they couldn't get it airborne because it needed both a new "carbonator" and new batteries. However, as a team they were better known for their winged aircraft flights.

Hamilton performed many spectacular, manned flights along the New York beaches in a Ludlow glider towed first by an automobile, then by various boats. Numerous reports by New York newspapers, a Scientific American pictorial (November 4, 1905, p. 356) and even international magazines documented the flights which were witnessed by tens of thousands of spectators:

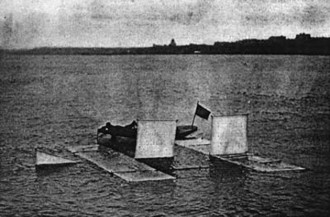

On one occasion, the tow-boat was forced to slow down for a passing ferry. Without forward pull, the kite glided down into the Hudson creating a spectacle somewhat reminiscent of the scene 100 years later when an Airbus ditched in the same spot:

Transition to Powered Flight & Whitehead Motors

Ludlow's aircraft were far from primitive. They had both vertical and horizontal control surfaces (elevator & rudder). He dislked the "tetrahedral" concept used by Alexander Graham Bell on his kites. Instead, Ludlow preferred a "dihedral" wing arrangement (which is what almost all aircraft still use).

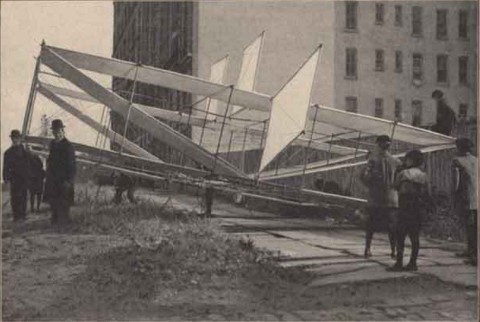

Ludlow's success with towed gliders (which he called "aerostats") encouraged him to move on to powered flight. For this purpose, he'd built a larger aircraft he called the "Flying Machine". The first known picture of the "Flying machine" without the motor appeared on July 22, 1905.

Soon, things progressed from wires, canvass & bamboo to oil & grease when - after a delay of two months - Gustave Whitehead delivered and installed an 18hp motor.

It was equipped with a long drive shaft typical of contemporary dirigable airships. It had counter-rotating (torque-neutralizing) propellers (a similar arrangement to Whitehead's own 1901 airrcaft). The motor was mounted well above the ground to allow longer blades and increase propeller efficiency, but below the wings' pressure point to enhance balance.

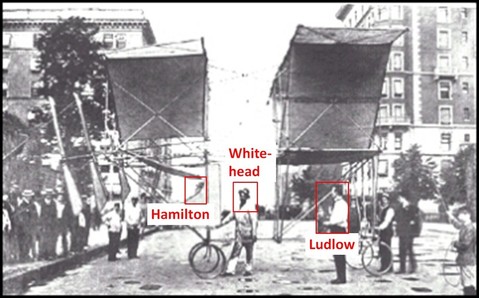

A photo taken taken in New York on West 79th St. shows Hamilton (slouching in the cockpit), Whitehead (wearing stained overalls and a hat, standing at center) and Ludlow (wearing a tie, at right) with the aircraft and its newly-installed motor:

[For earlier photos of the unfinished aircraft, click here.]

In Jan. 1906, Ludlow helped organize the Aero Club of America's first exhibition in New York where Whitehead was an exhibitor. Ludlow displayed a model there model there, not far from Whitehead's photos. At another show later that year, Ludlow himself also exhibited a model aircraft of his own making.

Early in 1906, Ludlow performed further flying experiments on the Hudson River by towing his airborne apparatus behind boats with Hamilton at the controls.

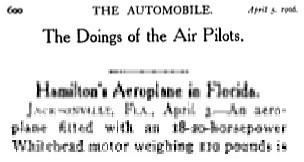

For Easter 1906, the Jacksonville Automobile Club (Florida) invited Ludlow and Hamilton to appear at their races on the beach there. They brought several aircraft with them. Several magazines reported, one of the aeroplanes was fitted with an 18-20hp Whitehead motor:

The Automobile, April 5, 1906, p.600

(Automotive Industries, Vol. 14)

"Hamilton's Aeroplane in Florida.

Jacksonville, FLA., April 3 - An aero-

plane fitted with an 18-20.horsepower

Whitehead motor weighing 110 pounds..."

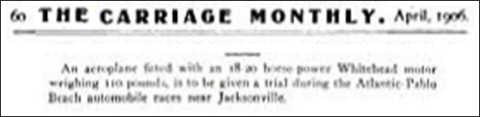

The Carriage Monthly, April 1906, p.60

(Motor Body, Paint & Trim, 1906, Vol. 42, p.404)

"An aeroplane fitted with an 18-20 horsepower Whitehead motor

weighing 110 pounds is to be given a trial during the Atlantic-Pablo

Beach automobile races near Jacksonville."

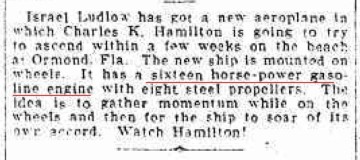

A New York newspaper makes it clear, it was Ludlow's wheeled aeroplane:

Brooklyn daily Eagle, March 26, 1906, p.12

Tragedy at the Ormond Beach Races

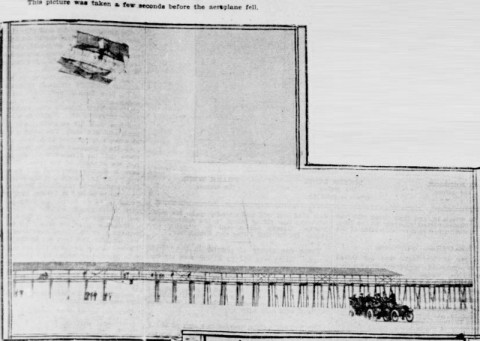

Hamilton started by flying a small glider, crashing it first into the surf, then later into a telegraph post next to a house. With the smaller glider now destroyed, Ludlow decided to fly a larger glider. It collapsed under the strain of being towed by two steam-powered cars. He crashed it into the beach from a height of 200 feet. As a result, he was paralyzed for the rest of his life.

Ludlow, Editor of Aero Club's First Publication

Despite his paralysis, Ludlow contiinued his involvement in aviation. As a member of the Board of Directors of the American Aero Club, he edited and co-authored their 1907 aviation progress summary entitled "Navigating the Air" The book includes articles by himself, Chanute, Herring and many others. In his own article entitled "Experimental flights with a Man-Carrying Aeroplane", he described both his experiments with kites and his attempts to achieve powered flight.

While working for Ludlow, Hamilton had survived a total of 63 crashes (some reports claim is was as many as 150 crashes). After Ludlow's crash and serious injury, it was apparently time for Hamilton to move on.

Hamilton first concentrated on flying dirigable airships (1906-1907). He then switched back to heavier-than-air machines in 1908. On June 13, 1910, he became instantly famous when he won a race along the railroad line from New York to Philadelphia and back. (His old boss, Ludlow, now confined to a wheelchair) watched the entire race out a window on a special train which followed the race.

Hamilton became a daredevil pilot for the Curtiss Show Team (1908-9). Glenn Curtiss once described him as "the most daring pilot in the world". After an altercation with Curtiss, he started performing on his own at air shows around the world (1910 onward). But he stayed in touch with Ludlow: When Curtiss tried to prevent Hamilton's appearance at a show he was organizing, Hamilton hired Ludlow to be his lawyer.

Ludlow, Director of World Fair's Aeronautical Exhibit

After he'd convalesced and started adjusting to life in a wheelchair, the Aero Club of America elected Ludlow to be Director of the Aeronautical Exhibition in Jamestown, Virginia, at the Tricentennial World Exposition to be held from April 15 to December 1, 1907. The exposition was to include

- a static aeronautical display,

- a congress of aeronauts,

- live demonstrations of airships and

- a Scientific American Cup for the best heavier-than-air aircraft.

A budget of $15,000 was provided to erect the first ever building devoted solely to an aeronautical display.

US Navy Sponsors Ludlow's Aeroplane

At the time, the US War Department was starting to get interested in aerial capabilities. It approached Ludlow about participating in his experiments.

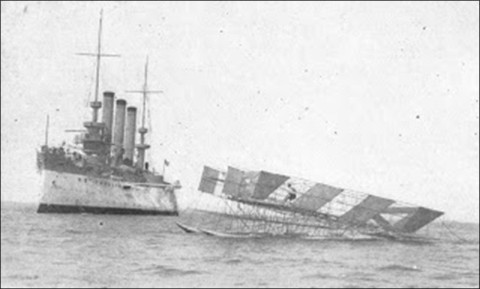

The US Navy assigned Capt. Thomas T. Lovelace, a hero of the war in Panama, as a liaison to Ludlow, appropriated ten enlisted men to assist building a new airplane and even placed a tug-boat, a torpedo cruiser and a battleship at his disposal. The US Army Signal Corps. also assigned a liason officer, Capt. Chandler, to the project. The new aircraft was to be a hydroplane which could either be towed by a ship or use its own onboard motor. (As such, it was the first Navy aeroplane.)

Wheeled Version at St. Louis Event

Ludlow's new staff pilot was J.C. ("Bud") Mars. The new machine was demonstrated in September 1907 at the Jamestown Exposition. During the first trial, it was pulled by the Navy tug, "Potomac". On the second trial, it was towed by the torpedo cruiser "Gwinn". Operations were directed from the deck of the Battleship "Missouri". On some of the flights, Mars was at the controls; On others, it was Lovelace. However, unlike the flights in New York, the Flying Machine failed to get airborne at the expo.

Part of the expo was the Gordon Bennett Air Races & accompanying Scientific American Cup (for heavier-than-air aircraft) held in St. Louis, Missouri (Oct. 21-23, 1907). Ludlow shipped his plane there to take part. It too, was equipped with a Whitehead motor (Ludlow entry, aerofiles.com).

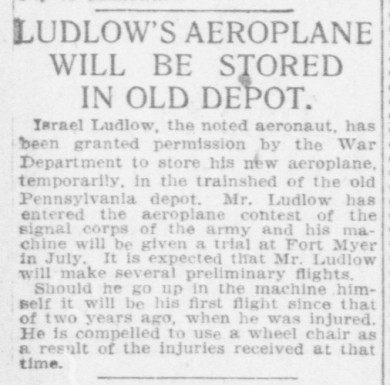

Unfortunately, the machine was damaged by apparatus designed to heat one of the balloons and was unable to compete. However, Ludlow was invited to officiate as starter of the balloon race. A photo of Ludlow's flying machine in St. Louis (with Ludlow in front of it) was shown on the front page of the Washington Times:

Ludlow & Others Lectured at Aeronaut's Congress

Ludlow immediately returned to Jamestown to run the Congress of Aeronauts.

Famous aviation pioneers like Prof. John J. Montgommery and Augustus M. Herring (both of whom lay claim to powered flights in the 1800s), gave presentations, as did the Aeronautical Director of the exhibition, Ludlow, himself.

After the Congress, one last attempt was made to get the Ludlow aeroplane flying. This time, the plane was roped behind six Cavalry horses who set off at a fast gallop. It, too, was unsuccessful.

On Dec. 1, 1907, the Jamestown Expo closed. As a whole, it was a financial failure, although the aeronautics exhibitions did well and were one of its few highlights.

Bud Mars Sets Out on His Own

After Jamestown, Bud Mars started a career as Superintendant, running the American Airship and Balloon Corp.. His former boss, Israel Ludlow, was Vice President and Legal Counsel.

Air shows were big business in those days, drawing huge crowds. The wealthy balloonist, Charles J. Strobel, was behind the scheme. team. Strobel was reported to have put $200,000 into the venture. His aim was to corner the air show market by contracting the best-known airship pilots to join his circus-like team. The result was, many of the "exciting air races" were actualy staged events. The venture soon fell apart. Mars lost his entire fortune in the process. He then went to work for Cleve Shaffer at the Oakland Aero Club in California. [Soon thereafter, Shaffer became Gustave Whitehead's West Coast dealer. It can reasonably be assumed, Bud may have had something to do with making that contact.]

Early in 1910, Bud joined the Curtiss Show Team and gained fame across the USA and around the world as a daredevil stunt pilot. When America entered World War I,the earlier contacts Bud had gained while working for Israel Ludlow came in handy. Bud became an aviator with the US Army's Signal Corps. (the predecessor to today's USAF). Bud died in 1944.

Ludlow flies at the Smithsonian - powered by Whitehead

Ludlow continued to build powered flying machines. After first setting up his workshop in Washington DC near the Whitehouse (at 1318 L St.), he soon got lucky. President Roosevelt decided to beautify the Mall by demolishing the Pennsylvania Railway Building. The US War Dept. allowed him to use the abandoned Building (on the corner of 6th St. & B St.) as a new workshop until demolition began.

There, he prepared for the military's aircraft trials at Fort Myer to be held that summer. (That's the event which made the Wright brothers famous in North America.)

The War Department appears to have been somehow involved in Ludlow's project:

Col. Bromwell, Chief of Public Buildings and Grounds, allowed Ludlow to use both the Mall and the area adjoining the White House for flight testing!:

Ludlow's luck soon faded. In early May, 1908, his brother died suddenly. Two weeks later, the Wright brothers published the first photos of their aircraft in controled flight.

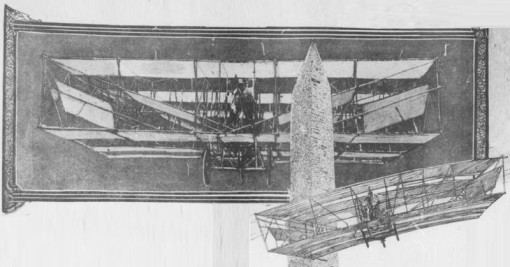

Once finished, Ludlow took his new flying machine out onto the Washington Mall - a long strip of parkland at the city's center. He started his takeoff-run at 6th St., heading south. Anyone who knows Washington DC will appreciate what an interesting place that is to perform a takeoff. Ludlow's plane took off exactly in front of the Smithsonian Institute's main entrance! (Ludow's workshop on 6th & B Sts. was on the opposite side of the Mall from the Smithsonian.):

The Whitehead-powered aircraft briefly got airborne on July 4, 1908 (a public holiday in the USA). A crowd of almost a thousand people was watching:

The flight was only brief and can hardly be referred to as a "successful". However, the Washington Times thought it was:

Immediately prior to the flight, the engine had performed well in run-up tests, creating 100 lbs. of thrust - enough to sustain the aeroplane:

However, shortly after rotation, the propeller shaft broke and the plane settled back down. Clearly, Ludlow was still using the same Whitehead motor he'd had in Florida:

Ludlow was very fair about it. He explained to the press that it was his own fault. He admitted ignoring the manufacturer's instructions in an attempt to save weight by replacing the 75lb. fly-wheel with his own 30lb. fly-wheel.

Apparently, the experience of gettig airborne, only to have the motor-shaft break, inspired the pilot, Robert S. Moore, who went on to design several aircraft motors, sold under the clever brand-name, "Moore-Power".

Ludlow went straight back to New York to get money and another engine. But he wasn't able to get his aircraft refitted in time to compete at the Fort Myer trials. Instead, he showed up there alongside General Allen, Chief of the US Army's Signal Corps., and toured the grounds. It was at those trials that the Wright brothers finally gained acceptance and made their breakthrough, establishing themselves as the new leaders of the US aviation scene.

Litigation & Politics After the Wright Patent Award

In August, 1908, Ludlow's team shipped his aircraft to Brighton Beach, New York, to participate in a serious of competitive tests against the machine of Henry Farman, which had been brought over from Europe. Apparently, Farman and Ludlow found common interests.

Ludlow soon used his military contacts to offer Farman's machine for sale to General Allen (US Army signal Corps.). The Army declined because it had just selected the Wright brothers' plane for their uses. Soon after, the Wrights applied for a writ to prevent Farman from flying in the United States at all. They even demanded that his aircraft be impounded or that he pay $6,000 per WEEK to be allowed to fly. He paid.

That's how Ludlow ended up as Farman's lawyer. For the next several years, Ludlow was indirectly the spokesman for the anti-Wright movement. His court arguments and statements were published in the magazine, "Aircraft", and all its issues (2/10-2/11) can be read online by clicking here.

Ludlow officiated at the 1908 Morris Park Aeronautics event (where three Whitehead-built aircraft were on display) as a referee. The following year, it was announced, his man-carrying kite from his earlier beachside experiments would be on display.

1909 was also the year Ludlow introduced a new airplane design. It was patented and guaranteed to be immune to Wright brothers' injunctions. A syndicate of wealthy Aero Club members was formed to back the venture.

Ealry 1910, Ludlow was consulted by Wall Street's financial pioneer, Charles M. Schwab, about producing a new generation of 200-300hp aircraft motors. [About this time, Gustave Whitehead also produced a motor of similar horse power. Any connection has not been investigated.]

In 1910, Ludlow was also elected to the licensing committee, responsible for issuing pilot's licenses.

After Ludlow spent a few days in summer 1910 with John J. Frisbie, advising him on his aircraft, the two decided to form what they called an "Aviation Trust". A company, the "Aviation Co.", was formed. The idea was to pool all the show pilots in the country and foster peaceful co-existence as an alternative to the bitter litigation which was consuming the flying community. Well-known pilots such as Charles Hamilton, Thomas Baldwin and four of the Wright Flying Team were enlisted in the venture. Sadly, Frisbie was killed the following year in a plane crash and the venture ceased.

In 1911, Ludlow founded the "Aviation Film Co." for the purpose of marketing aviation photos and movies. In 1914, Ludlow's new aircraft, the "Inherent Stability Machine" was finished and taken to a Long Island Airport for testing. That year, Ludlow was also one of the backers of a round-the-world air race. Furthermore, he successfully lobbied Franklin D. Roosevelt (then Assistant Secretary of the Navy) to have the US Navy select aircraft via competitive trials.

In 1912, he was legal counsel of the Bull Moose Party.

And in 1920, Ludlow was President of the "Aeronautical Equipment Co.". on 42nd St. in New York. By then he'd obviously slowed slowed down a bit. A theater play he'd written in 1906 while recovering from his accident, was being performed at the time.

Why so Much Information About Ludlow?

Some aviation historians have alleged, after 1897, Gustave Whitehead was apart from the mainstream of the aviation community. Curiously, their histories then go on - perhaps unknowingly - to list most of Whitehead's customers.

One customer rather conspicuously not included in most aviation histories is Israel Ludlow. Ludlow was described in the May 1910, Edition of "Aircraft" Magazine (p.108) like this: "There are few men as well known in aeronautic circles [ ] as Israel Ludlow. [H]is genial, cheerful disposition ever prevails, and in the very large number of people he knows, he has no acquaintances - only friends".

It's hard to find a more central figure in early US aviation. And, alongside Prof. Albert Zahm and Glenn Curtiss, it's also hard to find a more prominent and eloquent proponent of legal positions counter to those espoused by the Wright brothers. And yet, Ludlow, who launched the careers of famous aviators, shaped the course of leading organisations and wrote one of the first comprehensive books on aviation progress is conspicuously absent from most chronologies.

Israel Ludlow